2010년대에 막 활동을 시작한 젊은 미술가들은 지난 세대의 미술가와 전혀 다른 미디어 환경 속에서 성장기를 보냈다. 과잉된 IT 열풍과 PC방 문화, 그리고 스마트폰의 보급은 실제 지형을 대체한 포털 사이트의 지도 서비스, 검색을 통한 맛집 탐방과 웹툰 감상 등의 일상적 유희, 심지어는 정치적 입장을 드러내는 발언의 기회마저 SNS를 통한 간접화법으로 변환시켰다. 실재계의 두툼한 부피를 손바닥 안에서 완결시킨 이들의 삶은 마치 게임 속에서 현현된 가상의 지형을 돌아다니며 아이템을 사 모으는 게임의 시나리오처럼 보인다. 즉, 이들의 세상은 미디어로 굴절된 신체를 통해 다시 구현된 감각의 집합이다.

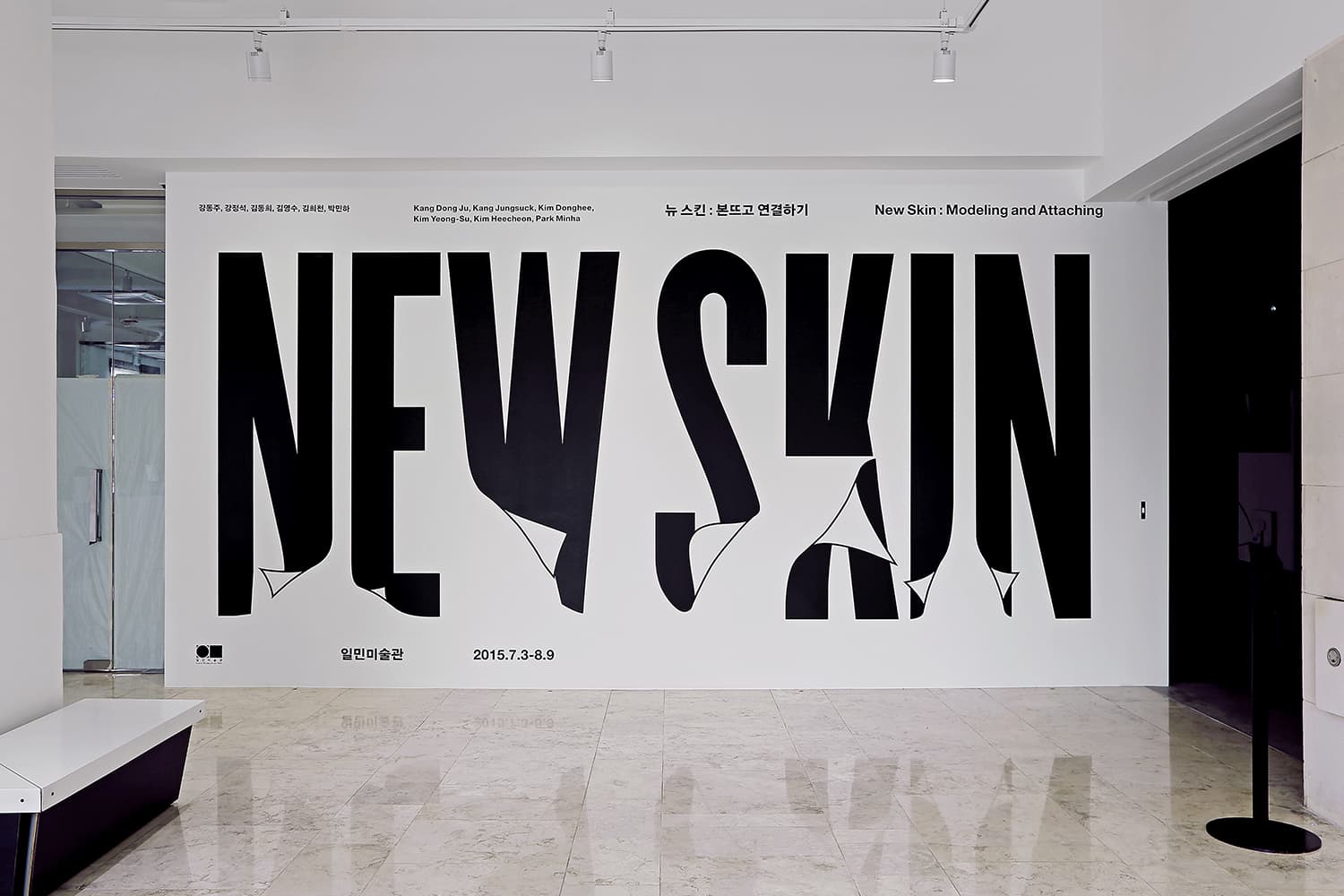

단순히 세계를 매개하던 인터넷이 스마트폰을 통해 실재계와 아예 뒤엉켜버린 지금, 새로운 세대의 미술 속에서 그러한 모습을 감지할 수 있지 않을까? ‹뉴 스킨: 본뜨고 연결하기›는 이러한 질문에 대해 단서를 찾기 위해 새로운 세대가 관찰한 세상의 외피가 어떻게 미술 안으로 변용되어 흡수되고 있는지 살핀다. 이들은 허구의 지형을 구성하는 시각적 외피를 도드라지게 함으로써 얻을 수 있는 어떤 숭고를 탐구한다. 그러나 그 숭고 역시 실존한다고 쉽게 말할 수 없는 가상의 영역에서 발현한다.

입체 모델링 소프트웨어인 3D MAX를 이용해 공간의 본을 뜨고 이어 붙여 가상의 공간 내부를 탐험하게 하는 김희천의 작업은 친구를 배웅하는 지하철 속 일상의 여정을 평범한 스마트폰으로 기록한 강정석의 시각-피부와 연결되고, 서울 안에서 실제로 이동한 경로를 눈에 띄는 요소로 나눈 뒤 데이터베이스화하여 손 그림으로 녹여내는 강동주의 작업은 개인의 이동뿐 아니라 삶에 제반 한 여러 가지 결정의 순간을 보드게임 플레이 하듯 임하고 있는 김영수의 작업과 연결된다. 박민하의 작업이 모든 가상의 스킨을 실제로 이용하며 전쟁을 벌이는 — 전쟁 역시 게임의 일종이자 가상의 내러티브다 — 미군의 훈련장과 할리우드 영화 기술 사이의 변주를 관찰한다면, 김동희는 다섯의 작가가 구현하는 감각을 전시장 안에 재현하기 위한 최적의 덩어리를 설계한다.

고고한 미술의 연대기 속에서 이러한 시도의 의미는 무엇일까? 제가 속한 시대의 형태를 겉으로 드러내지 않는 방식으로 드러내기 위해, 명징한 깃발 아래에 모여 함께 미학적 매니페스토를 외치던 선배의 방식을 데이터 단위나 혹은 아이템으로 체현한 후, 저마다 설계한 진공의 타임라인 안에서 공진하는 미술의 형태를 시험하는 오늘의 미술. 과연 그 징후는 화이트 큐브 안에서 어떻게 구현될 수 있을까?

참여작가

강동주, 강정석, 김동희, 김영수, 김희천, 박민하

장소

일민미술관 1, 2 전시실

주최

일민미술관

전시기획

함영준

연계된 프로그램으로 바로 가기(https://ilmin.org/kr/program/newskin-program/)

웹 플라이어 바로 가기(https://ilmin.org/webflyer/newskin/)

It seems it was already in mid 2000s that the art trend named “post-Internet” was recognized as the “next generation art”. Mainstream art had started collecting Internet images that can be seen anywhere by turning on the computer. Such trend brought about a confusion on the past system of critique that had sought to distinguish art and non-art. There were consistent complaints from the older generation on the several key-images that constitute the visual system of image archives such as Tumblr. In particular, when cheap Internet images are layered on top of the emergence of an unprecedented “insignificant” generation called hipsters, post-Internet art is regarded as the symbol of a trivial era.

The media art of late 20th century, the direct senior of post-Internet art, in a sense, was able to safely enter the insides of the art scene as it had a clear objective of appropriating new media to expand the denotation of art. But it quickly descended to an interactive culture (design) business mediating fascination to the audience, and was no longer able to perform any critical significance. When this is seasoned with a SF narrative as the likes of a fin-de-siècle decadence upon the future, nothing could better fit the carefree comment that media art is the art for everyone.

However, there certainly is an enchanting aspect to post-Internet art that is different from the past media arts. Post-Internet art rakes all possible images remediated through the Web, generates a massive archive, and produces new images in the manner of assembling a puzzle to kill time. Such stylistic trait is premised on the images naturally produced by a surplus restlessness that is overwhelmingly plentiful enough to paralyze the utilitarian function of the Internet. It thus does not intend to become art in the first place, and it doesn’t matter if it indeed is not art. Just as subcultures such as surfing, skate boarding, and hardcore punk had left behind their corresponding visual cultures, the term “post-Internet” itself takes on the form of everyone sharing the visual rhetoric that was once towed forth by the online experienced and talented who are fluent in the Web literacy.

It is media-digital technology such as Mode 7, early 3-D technology, matte filming, and duplicate images degraded by the Internet that post-Internet art in the West has mainly dealt with until now. This is because credentialed artists such as Harun Farocki and Hito Steyerl stood at the center of discourse. In a sense, they had become the new gurus of art for having faithfully answered the request of the mainstream art scene to please don an alibi as an art.

They investigated the nature of digital technology to “read” the images on the Web, and applied its various mechanisms in political situations through a series of video masses that were presented with rather heavy artist statements.

They usually proceeded to the conclusion that “because the nature of Internet images is such and such, I support them”. Then the vocabulary of these masters were brought into Korea in rampant mistranslation that they “severely criticize machine civilization”. For instance, the “poor images” on the Internet were, for Hito Steyerl, the “cyberpunk” of the 2000s. As the hippies of Silicon Valley in the late 1970s dreamed of utopia and clung to computer technology, or as the point when “Marxism” started to invade “cultural studies”, Steyerl designates low culture as the counter concept of high culture and asserts that degraded digital images are its representatives.

Looking back, it seems post-Internet art has progressed mainly in two directions. One would be the way of investing the cheap and vernacular Internet images with the traditional authority of art, and the other is to drag the former images of artistic authority down to the context of floating around on the Internet, where all images cannot be but flat due to the monitor.

Then in Korea where post-Internet art saw a rather belated bloom, what does the art look like? In Korea where the Internet is provided worldleading infrastructures, how does the Internet meet the arts?

Young Korean artists of the 2010s grew up in a media environment completely different from the previous generation. Since the advent of an unusually excessive IT fever and PC room culture, the everyday of students after school did not mean merely doing homework, reading books, or playing ball with friends. Instead, they started accessing the newly generated reality. This was a natural flow of events. When housing environment centered on apartments, its surrounding economic power relations, private education, and other distorted tricks of life finally bloated the reality to its fullest, the density could not but create cracks. Young children squeezed out through the gap and ran off into the world of fantasy inside square LCD screens.

In the meanwhile, the otaku culture from Japan parasitized on the closed foundation of Internet. However, this was not only because Korean Internet was simply a network functioning as a utopia where realistically impossible tasks can be realized. To be precise, this was possible because it was on the Internet that people who had not been able to find a suitable form of play in reality found others with similar tastes and shared the database they had accumulated. However, the ply of the everyday that Koreans had to face was not sturdy enough for them to bear that world of illusion. Ever since StarCraft served as a common ground between those who had played pool with neighborhood friends and those who worship Evangelion, “that subculture” once operated by a few computer junkie kids also lost a place to hide. The world of fantasy that had started out as a copy or alternative of reality, at some point, was entangled with the reality itself.

After about a decade since the “general public” was exposed to Internet, almost no one remembered whether living the life of reality and fulfilling its tasks preceded wandering around illusion as a form of play, or vice versa. Illusion took after the reality that freakishly accentuates efficiency, while reality processed the energy from illusion to meet the “public taste”. Big Web portals calmly and persistently redefined Koreans as a proper noun, and the “weird stuff” that had been flowing from the Web into the reality was embraced as (actually an even weirder, such as googling “Naver”) “the norm”.

When smartphones and SNS culture were added on top of all this in late 2000s, the world entered yet another phase. For instance, the mobile experience of gourmet tours through Web portal map services did not simply mean employing the functions of the Internet. Daily experience now took on a different form, having shifted from saving the body’s direct sensations on the brain to saving the images shot with smartphone cameras —a device synchronized with the body— on timelines of the online self. Such lives that have completed the full volume of reality in their palms were no different from the lives of game characters that roam the virtual topography of PC games to collect items. Living as if one had the option of choice when one does not, in a world where nothing is experienced even when it can be experienced. Thus, the body was no longer the body it used be, but a hologram created by light refracted through the prism of media.

Ever since the Internet was synchronized with reality, Korean Internet has constantly controlled the world outside the monitor. Citizens picked up the items of bicycles or hiking shoes and cleared the missions of Gyeongin Ara Waterway and Dulle-gil tracking. While entertainment shows on cable TV may slip otaku jargon in their subtitles, for the middleaged that frequent KakaoTalk, the terms were no more than interesting and trendy vocabulary that today’s young people use. A world where the people that always have be online share hundreds of images everyday among themselves. A world where only a large mass exists, a mass of numerous daily timelines broadcasted live through numerous selfies. A world where everyone can observe everyone. A world where everyone shares the same hot search words of the moment, the keywords that are updated every second by the Web portal shared by all. This is the world today’s Koreans live in.

Rather than the seemingly wicked low-resolution images of overseas Internet image archives, off the wall images that refer to nothing are now saved on Korea’s Internet in a desperately perfect posh structure. They are all high-end images that have unintentionally become cheap. This resembles the new town that has realized futile presentation-purpose functions through polished finishing during the past decade that Seoul city has spent on redeveloping its downtown. The spectacle that has jumped out of the monitor, one that consists only of its skin, floats around in the real world while people search for evidence of their own presence through the experience of taking its photos and uploading the images on KakaoStory.

Therefore, looking for “post-Internet art” in Korea is not a task that can be performed by introducing the masters of the West and seeking to share awareness of problems and the like. Because the Korean Internet is changing more thoroughly and at a pace much faster than art, Korea is where the absurd delusion to catch up with the speed of the Internet through art can actually become an ingredient for the art. In order to embrace a world other than the Internet, there is no other feasible method than to use the Internet’s grammar; and in order to understand the Internet, we can only model and connect the skin of the real world that reflects the Internet’s grammar.

Now let us take a few steps back and ask the following questions. Artists of this new generation grew up amidst eventful ups and downs of the Internet. How do they now perceive the world? In what kind of way do they reflect and represent the reality that now embraces the new domain called the Internet? New Skin: Modeling and Attaching invites six artists that investigate the virtual’s sublimity that can be attained by accentuating the visual skin of the fictitious topography. Resonating in each of the vacuum timelines that these artists have designed, toward what direction is this art form headed?

Artists

Kang Dong Ju, Kang Jungsuck, Kim Donghee, Kim Yeong-Su, Kim Heecheon, Park Minha

Venue

Gallery 1, 2

Organized by

Ilmin Museum of Art

Curated by

Youngjune Hahm